Exploring the Unseen

A series of interviews of Artists and Speakers featured at the CODAME ART+TECH Festival [2018] by Irene Malatesta

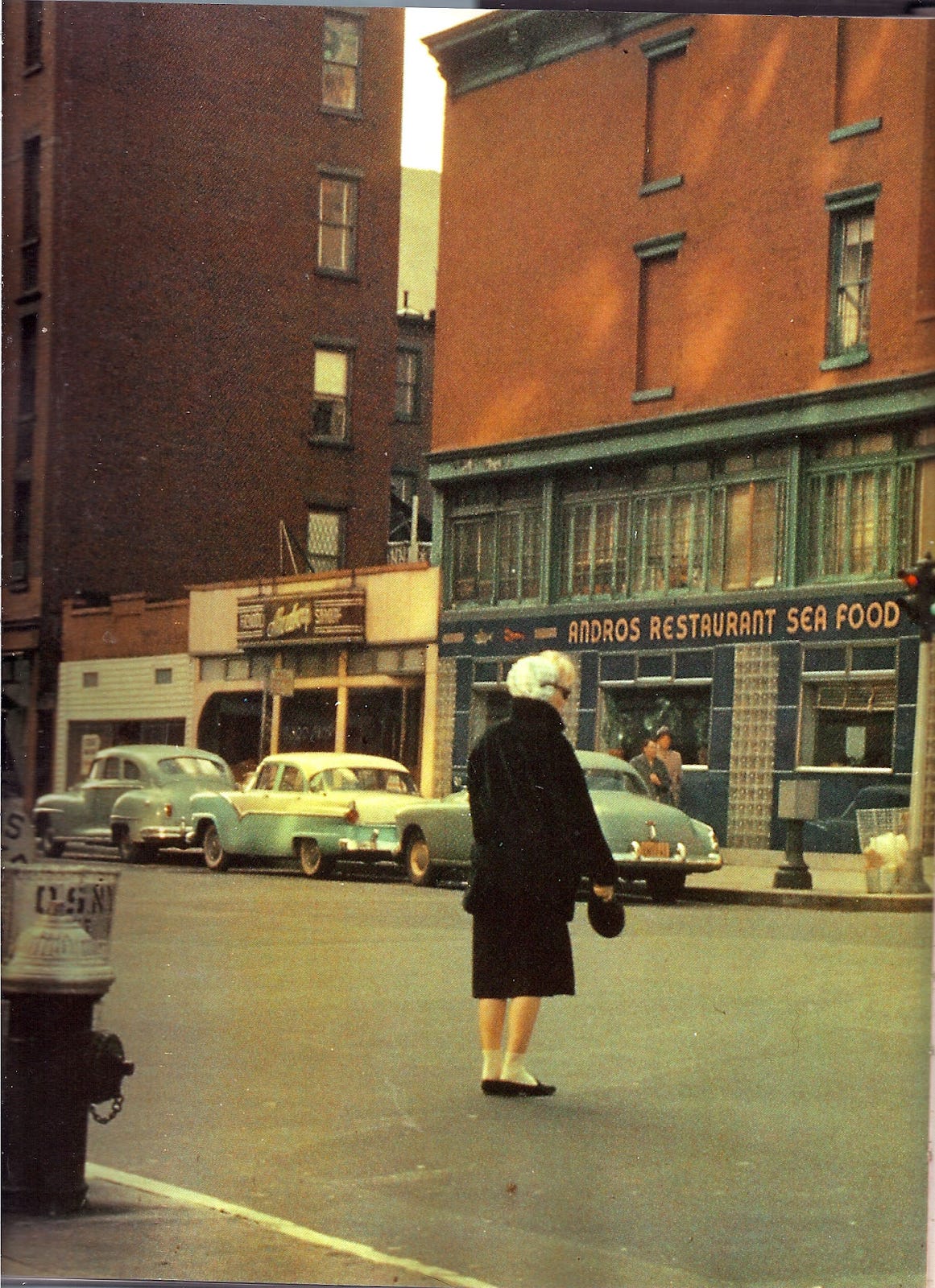

Norma Jeane incognito in Los Angeles. Photo by James Haspiel.

When considering multimedia artist Norma Jeane, the first impression that strikes is one of mystery and denial. Norma Jeane is the pseudonym of an Italian artist who does not wish to be identified. Where many discussions of an artist’s body of work might begin with personal biography in an attempt to understand the human experience that led to creating the work, that won’t do in the case of the elusive, cerebral, and multi-talented Norma Jeane.

This is entirely by design. Having chosen one of the most famous women in the world as a namesake (Norma Jeane Mortenson Baker, who you might know better as Marilyn Monroe), the artist Norma Jeane has built a 25-year-long career on the idea of making that which is typically invisible, visible, and vice versa.

This endeavor — to expose the unnoticed while erasing the expected — has been composed of a few different recurring elements. Multiple paths lead to this end, but the name is a helpful starting point. When I met with Norma Jeane this month via video chat, he explained, “What was really interesting and fascinating to me about Marilyn is not Marilyn but Norma Jeane. The fact that she actually split her life in two, had a terrible beginning, very tough and sad, and when she actually found success, she needed to split her personality to do it. [She was] such a complex person, who ultimately represents the most successful pop icon, which is something so simple. I’m also super interested in what’s normal, in everyday life, everyday objects.”

One might describe pop icons as the closest that human beings can become to “everyday objects.” Populating the media landscape and entertaining us from a distance, they are adored yet somehow, not valued in an individual sense due to their ubiquity.

Norma Jeane points out that often, what has the most value in an objective sense is often thought of as something that is extremely rare or strange, and that everyday “usual” objects aren’t typically examined closely: “[We] don’t consider them in an analytical way because they are just the landscape around us. But, in fact, they can be super complex, as though there were a ‘backstage’ area of reality.”

Given the amount of time and effort many people spend talking about, sharing, and otherwise engaging in the creation of pop culture and icons like Marilyn Monroe, Norma Jeane has an undeniable point. The persona, he explains, is a way to engage with the “dark side” of culture.

Self, Community, Potlatch, and Ritual

Two major threads are present in Norma Jeane’s work. The first, as evidenced by the chosen pseudonym, is a denial of self, celebrity, and the meaning of an artist’s biography. He is emphatic about this point, stating, “I didn’t want my personal biography to have anything to do with the art that I was making.”

The second major thread is the concept of “potlatch,” or “squandering,” a concept this artist has approached via an anthropological lens and a philosophical lens, engaging with the work of French anthropologist Marcel Mauss and French intellectual Georges Bataille, respectively.

A potlatch, loosely defined, is a gift-giving ritual event, practiced within the indigenous cultures of the Pacific Northwest Coast of North America. Groups engaging in this practice include tribes in British Columbia, Kwakiutl and Tlingit, among many others, and within these groups, the potlatch represented the primary system for the distribution of community wealth. In these frequent important, ceremonial events, gifts of food, property and art were exchanged, and sometimes destroyed. This was both a show of wealth and power, and an important rebalancing of resources within the community.

Norma Jeane says that while the practice of potlatch has mostly been studied in just a few North American tribes, similar rituals actually extend to many other places around the world: “In different tribal cultures they have sort of similar rituals. In Polynesia and other areas, the potlatch was mostly based on gifts, the ritual in British Columbia was mostly about destruction and squandering, not giving. [Part of the] act of giving a gift was to give a proof that you are not attached to property.”

Reflecting on the different purposes of the potlatch, Norma Jeane says, “This was a ritual that has a few functions. In my view, the most important one was to fight the conflicts of interest in a small society. It’s very easy for the richest person to become the chief. While normally in those tribes, if there were more than one competitor for the role of chief, they would challenge each other, in destroying belongings. They’d actually demonstrate it publicly, [showing that they were] able to renounce goods and privileges, [and one person] was then appointed as the one most fit to have a public role and public responsibility for everybody else in the tribe.”

In this social ritual, renouncing possessions is required of anyone who desires community power and social standing. This act of destruction or giving marries the attainment of social power with the renunciation of excess material wealth.

The ideas of self-erasure, denial of celebrity, and the potlatch are all closely related, and that relationship is vital to understanding Norma Jeane’s body of work. The concept of the potlatch contains many facets under one umbrella: a gift-giving event, an event where possessions are destroyed, and a public renunciation of materialistic attachment in the name of better service to the community. All of these ideas appear in direct conflict with the modern concept of celebrity and with the creation of art as an individualistic expressive activity within a capitalist system. When Norma Jean removes the presence of the artist as celebrity from the equation, he frustrates the expectations of a contemporary art world built on cults of personality.

He takes this notion further by collaborating with many others for most projects. Norma Jeane says, “Each time I develop a project, 90% of the time I work with other people, I build up a team, a collaborative team. The body of Norma Jeane is then composed of the people that actually work on each project. I consider myself as the initiator and the continuity of the Norma Jeane project.”

That physical removal of self makes it difficult for a work to be promoted or sold in a typical manner. It also makes it easier to uncover that “backstage” aspect of things that Norma Jeane finds so interesting. He explains, “If you are trying to create an event — a real event and not just a representation of something you want to communicate — you actually need, as the first choice, not to represent yourself. The representation of yourself, causes it to immediately become part of the work you do. Traditionally in art, and particularly in contemporary art, because of the art market, the biography of an artist is so important to add value to the artistic [output].”

When considered as a mechanism for perpetuating structures of power and contributing to a feedback loop of wealth inequality, celebrity, Norma Jeane says, “is actually a danger. …Giving somebody the power to modify the society, especially in small societies, is very dangerous. That’s why the potlatch rituals had greater importance than in our society.”

Consumer Rituals and Everyday Objects

Of course, modern capitalist society also has rituals; we may simply be inured to them and not focused on analyzing them in our daily lives: “We should also consider that we do have more complicated rituals that actually became part of the economical or social or political dynamic, so much that we don’t actually perceive them anymore,” says Normal Jeane. “The ritual of consuming, buying, et cetera; we could see some patterns of symbolic ritual in that.”

It’s those everyday rituals, alongside obsessive, addictive consumerism and the symbolic power of destruction, that have become important in Norma Jeane’s work, which has included examinations of objects like vacuum cleaners (as in Potlatch 3.1/A bout de souffle 1998, where several were connected by their hoses, inevitably destroying one another), to the performance of the increasingly isolated and ostracized ritual of the cigarette break (as in The Straight Story, 2008, where more than 1500 occasional performers smoked in transparent enclosures, transforming a typically private ritual into a living sculpture).

Norma Jeane. The Straight Story. 2008, installation view, Frieze Projects. Image courtesy of the artist.

Given the importance that many people place on objects as symbols of wealth, individuality, and social power, it is understandable that many will also feel and project strong emotions upon those objects. With the rise of “smart” objects, digital assistants that speak to us, and other machine learning technologies that seem to anticipate our every need, that emotional bond has only grown stronger.

Norma Jeane explores this phenomenon of people projecting their emotions on objects, imagining the feelings of objects, in a sense, inhabiting those objects with borrowed souls. When considering where they began working with objects in order to tease out certain emotional reactions from visitors and participants, he says, “My starting point was that artifacts and particularly machines are an incredible mirror of our humanity. We actually project on things that we, as a collective subject, create and that we consider completely separate from us. In fact, it’s a constant dialogue. We actually define our identity, most of the time, by comparing ourselves or reflecting ourselves in artificial objects, machines or patterns. [In that way,] society is a technological tool.”

The destruction of common objects, or subversion of their intended purpose (as with the vacuum cleaners of Potlatch 3.1/A bout de souffle), is calculated to draw maximum emotional discomfort and personal identification from human viewers: “[I] work a lot with the fact that we don’t realize that, but we actually have feelings for the objects. It makes no sense at all, but it happens. That’s why I was pretty nasty with common objects. The more I was nasty with the objects, the more people felt involved emotionally.”

The Legacy of ShyBot

For the 2018 CODAME ART + TECH Festival, Norma Jeane will present an interactive experience based on a project called “ShyBot,” a work that the artist declares operates on the exact same principles of human emotional identification with objects or machines.

ShyBot was initially conceived and presented at the inaugural Desert X biennial art festival held in the Coachella Valley in Palm Springs, CA, in February of 2017. It consisted of an “autonomous, self-driving, human-avoiding rover, solar powered, computer vision enabled and GPS tracker.”

Highly site-specific in that California is a place now associated with advanced and innovative technology, artificial intelligence, and robotics, the Desert X festival allowed Norma Jeane to work with other technologists to introduce an “advanced piece of technology into a situation which is completely uncomfortable.”

Taking inspiration from the Mars Rover, Norma Jeane considered a version of the Rover that did more than cruise around, recording and analyzing the landscape. What if, instead of an information-gathering emotionally-neutral mission, the Rover had an emotional mission? What if the robot chose to wander the desert because it wanted to be left alone, and the desert was a place where it felt most safe? What if the robot was…shy?

Norma Jeane, ShyBot, part of “Desert X.” Photo credit: Emily Berl for The New York Times. Source.

Norma Jeane recalls, “The idea was simple, to have all the sorts of sensors needed to have a really autonomous robot, that could decide where to go to avoid obstacles [and so on]. At the same time, [it could] detect the presence of living creatures. The moment that it perceived there was a living creature around, it would just escape. [That] basically made impossible to watch it at all. It’s just a little point in the middle of the desert, and if you approach it, it goes away immediately and fast!”

It’s hard to deny that the description alone of this robot’s behavior is endearing and even cute. Most reporters covering the exhibition seemed to feel that way; a journalist from the New York Times asked about the gender of the robot, even going so far as to assume that ShyBot was female. The artist, amused, said, “Well, I really hadn’t thought about that much. So I said, Yes. Why not? What’s incredible is that from that moment ShyBot was referred to as a female creature in articles, in TV, in the news. ‘She, she, she.’ Amazing.”

This additional layer of personification certainly reveals something of common gendered expectations. More interesting, though, may be the ways in which people apply stereotypes to soften strangeness and reshape it in an image that is more comfortable or familiar. Stereotypes, when applied to innovative objects, situations, or advanced technology, allow the layperson to become comfortable and thus regain a feeling of mastery over that which they cannot understand.

For the CODAME festival in June, Norma Jeane will present “an evolution of Shybot,” which he says will be “very different from a physical and technological point of view, but will put viewers in a similar situation, the same way that we feel for ShyBot, but for ourselves.”

The presentation at CODAME will feature a short film discussing the making of, and meaning of, ShyBot. Participants will be invited to watch the film while relaxing in a space equipped with “orgone energy” blankets (orgone energy being a sort of life force, or orgasmic energy, depending on who you ask, originally theorized by psychoanalytic doctor and philosopher Wilhelm Reich), custom made with the wool of rare black sheep from a flock in Sardinia, where the artist visited during his travels.

Still from the music video for “Cloudbusting,” Kate Bush, 1985. (source: YOUTUBE)

Though Reich’s ideas and experiments were dismissed by the scientific community (and even actively suppressed by the U.S. government), they continue to capture the popular imagination. Kate Bush’s 1985 hit song, “Cloudbusting,” refers to Dr. Reich’s attempt to create a machine that would control the weather and make rain by focusing orgone energy at the sky. Luminaries such as William S. Burroughs, J.D. Salinger, Jack Kerouac, Sean Connery, and Kurt Cobain have all been said to have tried orgone therapy for help with creativity, neuroses, low libido, or other assorted ailments. At this year’s CODAME festival, you can try it out yourself.

While visitors to the ART+TECH festival will be able to see and learn about ShyBot, the robot herself will not be making an appearance. Back in the Palm Springs desert, something happened that was, perhaps, inevitable: ShyBot disappeared for good. While a built-in GPS tracker allowed biennial-goers to follow the explorations of ShyBot in the desert, after several days the data stopped coming. Perhaps the GPS tracker broke; more likely, someone caught ShyBot and helped themselves to her parts.

In the news at the time, the reaction was again quite emotional. The organizers encouraged this: “Desert X” curator, Neville Wakefield, called the disappearance a likely “botnapping” and arranged missing-bot billboards and a cash reward. ShyBot, however, was never seen again.

The new installation is titled, “The Soft Machine,” a reference both to the novel by Burroughs, and the greater concept of human beings as “soft machines.” Interacting with all of Norma Jeane’s work, we consider ourselves in relation to systems, whether social, organic, digital or mechanical, connected by rituals and emotional exchange.